As Richemont sells Shanghai Tang, Hermes continues to back Shang Xia, Are Chinese Luxury Brands Doomed to Fail?

Does Richemont’s divestiture of Shanghai Tang mean that Chinese Luxury Brands are doomed to fail? Hermes backed Shang Xia might prove otherwise

Back in 2013, it was reported in Wall Street Journal that Financière Richemont SA, better known as Richemont to industry insiders, decided against selling some of its struggling business units, including pen maker Montblanc, and instead will increase their investment into each of the 20 brands within their portfolio. Some, like Montblanc have become success stories with the addition of a watchmaking concern; others are still struggling to find their feet four years later and among the first to go – Shanghai Tang.

Back in 2013, it was reported in Wall Street Journal that Financière Richemont SA, better known as Richemont to industry insiders, decided against selling some of its struggling business units, including pen maker Montblanc, and instead will increase their investment into each of the 20 brands within their portfolio. Some, like Montblanc have become success stories with the addition of a watchmaking concern; others are still struggling to find their feet four years later and among the first to go – Shanghai Tang.

The Richemont – Shanghai Tang’s relationship goes back close to 20 years. The Group first acquired a majority stake in 1998 before completely taking over the brand in 2008. At the time, the acquisition was considered to be strategic just when the luxury goods market started to peak in China.

A primer on Shanghai Tang

Since the early 90s, Hollywood celebrities like Demi Moore and Nicole Kidman have flirted with the Qipao or Cheongsam and perhaps, founder David Tang thought that a brand tapping into a zeitgeist of western upscale clientele would propel a brand with Chinese flourishes into critical and commercial success. Headlined by a body hugging dress of Chinoiserie design, Shanghai Tang was born in 1994, producing the iconic 1920s Shanghainese socialite uniform except that this time, it was interpreted for modern women. The formula appeared to work when in the late 90s, the era’s IT girl Kate Moss started to produce her own collaboration of Cheongsams with Topshop, coinciding with a trend of western celebrity appropriation of Chinese cultural dress.

Almost 10 years later, during a 2013 interview with Business Insider, it was reported that as the “global curator of modern Chinese aesthetics,” Shanghai Tang had managed to achieve 43% increase of global sales by 2005; fuelled by an expanded collection of not just Chinese-inspired fashion but also accessories and homewares.

Physically, Shanghai Tang operated a majority of boutiques within China (30 out of 45 stores) and at the time (2013), Asians represented 51% of the brand’s consumers with native Chinese forming the bulk while 49% went to a market of Westerners. Then, in the intervening four years, things started to go wrong…

Luxury Business Science 201: What went wrong with Shanghai Tang?

First, let’s just say that culturally, the cheongsam can be considered fairly analogous to a bespoke suit. If one were to follow the 1920s Shanghainese model, wealthy socialites would typically get measured and then fitted for a bespoke or made-to-measure qipao cheongsam. As a cultural garment, the raison d’etre of the qipao was to be as form fitting, emphasising the feminine attributes of her owner. An off-the-rack offering was possible but at those price ranges, you were could consider a bespoke version at your local and often, longtime seamstress.

Second, consider for a moment the odd cultural crossroads where you are marketing a brand to a highly nationalistic citizenry where a large number of your clientele are gwai lo 鬼佬 or lao wai 老外 and you begin to have a contradiction of cultural expectations which complicates potential brand direction.

Finally, the rise of millennials and the corresponding soft economies in which they have grown up have led to a bifurcation of expectations. On one hand, a group of millennials who do not harbour aspirations of status or pretense and the other, a group of millennials who do aspire to luxury but dollar for dollar would prefer clearly European luxury brands, as a result Shanghai Tang was placed in a confluence of increasingly tepid performance and certainly, they were not the sort of brand within the Richemont portfolio which was as easily understood like watches and jewellery (or for that matter, guns – Purdey, purses – Lancel).

For Richemont, Shanghai Tang just wasn’t a solid performer and given the different market variables, they sold the 23 year old brand to Italian fashion entrepreneur Alessandro Bastagli and private equity fund Cassia Investments Ltd.

What does this mean for foreign owned Chinese Luxury Brands? Are Chinese Luxury Brands doomed?

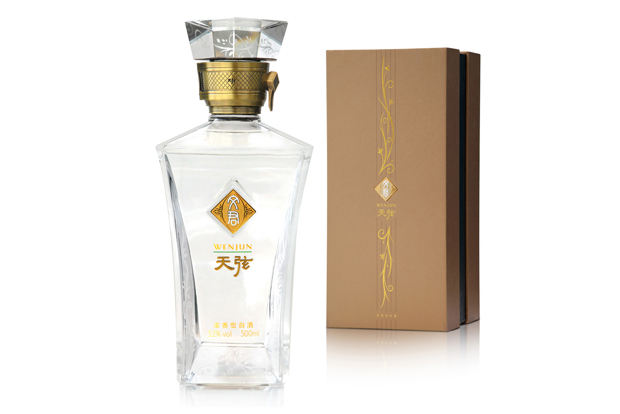

Richemont Group is not alone in their divestiture of a chinese luxury brand. Earlier this year, LVMH dropped luxury Chinese spirit label Wenjun. For some reason, luxury conglomerates practiced at marketing brands with a depth of history and tradition appear to be finding it problematic to market brands from China, even when they have the equivalent depth of Chinese history and culture; Case in point – The Wenjun Distillery, a premium white spirit or bai jiu 白酒 maker has a heritage going back to the Han Dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD), that’s over 2000 years of heritage. LVMH, itself a specialist in premium liquors through Moët Hennessy decided in January to drop Wenjun Distillery, having acquired a 55% stake in 2007.

What is not immediately certain is whether Chinese President Xi Jinping’s anti-graft measures are curbing consumption of premium liquors (traditionally a deal-making lubricant in Chinese culture) to such a degree or that China’s growing wealthy upper middle class are just not consuming luxuries at a pace that LVMH had projected (similar to the millennial issue with luxury goods).

Former British accountant and now luxury analyst, Rupert Hoogewerf began studying the Chinese market by establishing Hurun Report, a luxury research unit based in Shanghai in 1999. Over the years, Hurun Report and Hoogewerf have won numerous awards for their ground-breaking lists, among them an eye opening 2017 Best of Best (BOB) top 10 list which ranked popular luxury brands for women in China – the findings? Shanghai Tang was dead last. More tellingly, it ranked nowhere for men. As for Wenjun? It was not ranked on a list of top 10 bai jiu白酒 brands either.

In this context, Richemont and LVMH’s decision to sell the underperforming Shanghai Tang and Wenjun brands appear to be backed by strong evidence that both were not performing to expectations. But does this herald the end of the European adventure into owning Chinese luxury brands? Not yet.

How Hermès differs from Richemont: Shanghai Tang vs. Shang Xia 上下

In 2008 Hermès created Shang Xia. Unlike Shanghai Tang or Wenjun, Shang Xia is a bona-fide Chinese brand in that it is developed in China and helmed with a Chinese team (no foreigner direct it) and based on deep Chinese cultural roots and craftsmanship, that is to say, for all intents and purposes, Shang Xia is Chinese-made, Chinese-designed and Chinese-run but with capital injections from a French company. In fact, when Hermès CEO at the time backed renowned Chinese designer Jiang Qionger to start Shang Xia, the French maison had declared that they were not only not in a rush to breakeven but had pledged an ambitious capital infusion of US$10-15 million annually. Hell, Hermès long term objectives for the brand are baked into the name itself – Shang Xia 上下 literally means to grow up strong or Shang 上 (up) by putting roots down, ergo Xia 下 (down); and in founder/designer Jiang Qionger, Hermès found all the skillsets to incubate their revolutionary concept of fine contemporary chinese craftsmanship – her creativity extends through not just fashion but also painting, graphics, jewellery and furniture – in fact, the first Chinese designer to show her collection at a Paris furniture Salon. More tellingly, when French brands invite you to design their corporate headquarters and interiors, you know that your talents are beyond reproach. Most importantly, unlike Richemont or LVMH, Hermès is not in a hurry to “maximise shareholder value” – in essence, they’re taking their time to wait for the brand to literally take root and then branch out, organically.

“Shang Xia is a cultural investment project … [At other brands] the life of the project is five years or 10 years, at Shang Xia the dream is 100 years, 200 years.” – Jiang Qionger, Shang Xia Founder/Creative Director, speaking to Financial Times

Beyond the lofty ideals espoused by the branding, Hermès and Jiang literally took their time, seeking out genuine Chinese master artisans before they even considered their first boutique in Shanghai. In fact, in the last few years, a traditional Shanghai mansion, similar in spirit to the Hermès maison in Paris Faubourg Saint Honoré has been painstakingly rebuilt and renovated to host not only Shang Xia and Hermès but also a dedicated area focused on imparting knowledge of traditional Chinese rituals (e.g. the Pu-erh tea ceremony) and customs to visitors to the maison.

This traditional Shanghai mansion is home to Shang Xia

With dresses costing €4000 and this Shang Xia lacquered walnut-wood Da Tian Di rocking chair, €10,800, Shang Xia is playing the long game

As a brand, Shang Xia avoids the pitfalls of Chinese luxury brethren Shanghai Tang and Wunjun through sheer patience, unquestioning venture funding, an emphasis on genuine ancient Chinese crafts techniques and a carefully curated collection of limited products that are not for general sale, but auctioned through auction houses like Christie’s. While Hermès intends to break-even this year, it is too soon to say if the strategy for intentional blurring of lines between art and commerce is going to be successful, but LUXUO can say this, it is a singularly unique one, not even the most rarified of watch brands comes close. In an interview with Financial Times, Jiang states, “Shang Xia is a cultural investment project … [At other brands] the life of the project is five years or 10 years, at Shang Xia the dream is 100 years, 200 years.”

Truthfully, if Mao Zedong’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution decimated Chinese culture, tradition and history from 1966 until 1976. Shang Xia 上下 is quite possibly amongst its last defenders and preservers, even if they’re not successful commercially, Hermès is doing the world a big favour artistically and culturally – there is some great PR value in that, after all, Shang Xia is a perpetuation in that quintessential Hermès belief in craftsmanship, creativity, heritage and integrity – something which even some venerable watch brands have commoditised and automated.

Jiang Qionger, Shang Xia Founder/Creative Director

Shang Xia mahjong table

Business of Luxury: Does Richemont’s failure with Shanghai Tang provide an allegory for Shang Xia?

Richemont’s sale of Shanghai Tang does indeed cast a pallor over the viability of Chinese luxury brands but if anything Hermès’ carefully paced expansion in China has not only kept the French maison profitable but also retained that aura of ultra-exclusivity, a lynch pin of luxury retail and branding. It would seem that Shang Xia is being incubated and nourished in the same vein as its adoptive parent.

Richemont’s ignominious venture with Shanghai Tang was also the result of a confluence of increasingly exorbitant Hong Kong rentals (closing a flagship in 2011), over expansion and perhaps also, a misreading of a growing generation of millennials. That said, with Hermès expecting breakeven from Shang Xia this year and a jarring (Hermès not only never sells online but their website is similarly vague and opaque) eCommerce platform on Tmall that runs contrary to typical Hermès strategy, it is likely that this out-of-character decision is also the result of knee-jerk impatience of shareholders of the publicly traded company and it is anyone’s guess what will happen should Shang Xia fail to break even by year’s end.

Though no figures for the Shanghai Tang sale were released by Richemont, the brand was one of four labels that were under threat of divestiture since 2013: The other brands being Dunhill, Chloe and Azzedine Alaia. After announcement of the sale, Richemont Group shares were up 0.7%.