Go Behind the Fantastical Halls of the Cartier Manufacture

The Cartier Manufacture and Maison des Métiers d’Art offer a fascinating glimpse into the artistry behind their creations.

With a history dating as far back as 1847, it is hard to look beyond the momentous day when Louis-François Cartier took over his master Adolphe Picard’s workshop situated at 29 rue Montorgueil in Paris that has since sparked 177 years of splendour. The early days of the maison were focused on jewellery-making for an enviable group of royal clientele. It was not until 1904 when Monsieur Cartier’s grandson Louis Cartier created Cartier’s first wristwatch — the Santos — for his aviator friend Alberto Santos-Dumont.

While the watch was meant to be a functional tool for Santos-Dumont, little did Louis Cartier know that it would become one of the pivotal icons of Cartier’s history and alter the maison’s trajectory. Influence of the Santos watch proliferated and — slowly but surely — other era-defining watch creations such as the Tonneau, Tortue, and Tank came into existence. The ebb and flow of Cartier’s watches over the decades to come ultimately necessitated their own manufacturing facility, which finally opened its doors in 2001. Other facilities in the neighbouring Swiss Cantons form the greater Cartier Watchmaking Manufacture. The first steps of watchmaking begin with Glovier, situated in the Jura. Steel and gold watches are produced and assembled in Villars-sur-Glâne, located in the canton of Fribourg, while Cartier’s latest technologies are tested in Couvet. Cartier’s Maison des Métiers d’Art — located inside an old renovated farm — is a stone’s throw from the La Chaux-de-Fonds facility.

Nestled in the heart of La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, the Cartier Manufacture stands tall as a beacon of unparalleled craftsmanship and innovation. It is situated amongst the esteemed company, with the likes of Patek Philippe’s Crêt-du-Locle facility, the Gruebel Forsey atelier, TAG Heuer and Breitling’s manufacture and movement maestro La Joux-Perret, in and around its greater vicinity. It ushered in a new era for Cartier at the turn of the millennium as various functional bodies such as design, manufacturing, assembly and support were housed under the same roof. However, the significance of the Cartier Manufacture goes beyond that, as the fusion and concentration of time-honoured savoir-faire and cutting-edge technology breathe life into the iconic Cartier watches.

Unlike dusty or dilapidated workshops, the Cartier Manufacture is a state-of-the-art facility spanning 33,000m2 of space zoned for various departments within its metal and glass facade. Heavy industrial machines such as CNC machinery are housed on the first level, while an environment-controlled cleanroom is home to the calibre assembly and quality inspection teams. Other departments in the manufacture include the restoration, quality control, design, polishing and assembly teams.

From Paper to Metal

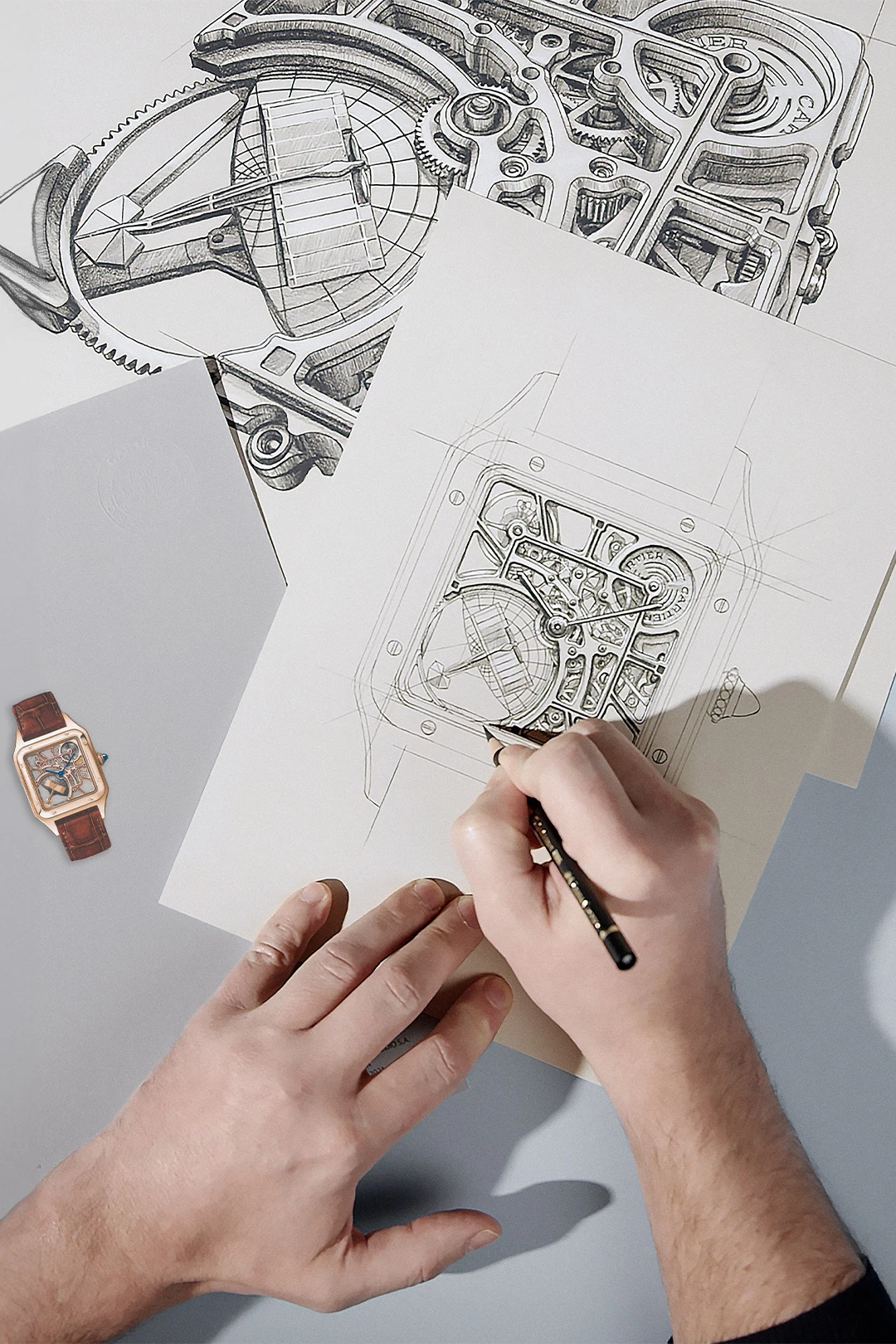

The life of a Cartier watch begins with an idea, more often than not ephemeral — easily lost — than concrete. And just as a picture paints a thousand words, there is no better way to articulate an idea than with a sketch. Armed with ideas from the marketing team, the designers interpret and translate them accordingly through sketches from various angles. It is here where the proliferation of imagination and creativity comes alive. Gouache (an opaque watercolour) further strengthens the sketches by introducing colours — such as coloured gemstones set on a yellow-gold case and bezel — to an otherwise black-and-white world. A quick tidbit here: while Cartier was under the tutelage of the recently-departed CEO and now chairman of Cartier Culture & Philanthropy Cyrille Vigneron for the past eight years, all sketches — whether for regular production or custom client orders — have to be personally approved by him. A signature on the bottom right indicates approval for the design teams to proceed with prototyping. Otherwise, it is back to the drawing blocks to refine the sketches.

Resin replicas are then created through 3D printing. It allows the development teams to assess the watch’s aesthetics, such as the curvature of the Ballon Bleu de Cartier or the suppleness of the Pasha de Cartier’s bracelet before actual working prototypes are created based on technical dossiers. This documentation is a critical part of the production process as — based on the expertise and skills required — industrial processes are being properly defined and mapped out by the industrial processes department. Furthermore, it allows the processes to be simulated, checked and fine-tuned accordingly to meet actual production quantities when they are later defined.

As we toured through the complex, several interesting areas caught our attention, spanning both traditional and forward-thinking techniques. On the archaic end of the spectrum lies the mineral crystal shaping team, which — according to Cartier — is an almost lost skill in Switzerland. Since a fair number of Cartier’s watches come in unconventional shapes — such as the Baignoire or famed Crash — mineral crystals are used instead of sapphire crystal, given their malleability to fit those cases. Rather than employing machines and technology to shape the mineral crystals, an artisan does it manually with a blowtorch until they are malleable enough to be shaped to different watch model specifications. Inspections along the way are done with the human eye, not machines.

On the opposite end of the spectrum lies the specialised machinery for dedicated processes, such as milling and CNC machines in the bracelet manufacturing department and quality inspection machinery. Those machines employed in the former department are responsible for fashioning bracelet links from metal bars. Up to nine bars can be processed simultaneously, with the simplest bracelet requiring 30 seconds per link, while more complex examples require up to 90 seconds. Since Cartier pays close attention to quality and reliability, inspections are done throughout manufacturing. An automated four-step test sees watches submerged in water and acid, and exposed to magnetic waves and extreme temperatures to ensure they are resistant to each element. If one is wondering how Cartier ascertained the reliability of its watch bracelet, there is a machine dedicated to wiggling the life out of it to ensure its structural integrity.

At the midpoint of the spectrum lies Cartier’s restoration department, which is in charge of restoring vintage Cartier watches and clocks. The highly specialised department represents one of the pinnacles of Cartier’s watchmaking might, as highly skilled watchmakers revive ancient pieces back to life. Whether it is a cosmetic or mechanical restoration, the team employs various techniques, from faithfully reproducing period-specific components found in archival blueprints to devising innovative solutions to solve certain conundrums.

Where Splendour and Dreams Come Alive

Inaugurated in 2014, Cartier’s Maison des Métiers d’Art is a stone’s throw away from the Cartier Manufacture. Unlike the gleaming architecture of the Cartier Manufacture, it takes up an old farm. Within the hallowed walls are even older artisanal techniques teeming with tradition, heritage and secrets brought to life through boundless creativity and imagination. Time is seemingly altered within the atelier as these age-old techniques are adapted and incorporated into modern executions that defy the usual codes of beauty. While there are many techniques, they are divided into three main categories: the art of fire, metal, and composition.

Enamelling — categorised under the art of fire — is a technique that needs no introduction. However, Cartier’s mastery across various techniques spanning the likes of and not limited to champlevé, cloisonné, plique a jour and grisaille enamelling deserves attention. Enamel first exists as coloured glass powders in paint form before being repeatedly fired in kilns (up to 10 rounds of painting and firing) at different temperatures to set or vitrify it. While enamel is mostly contained in the watch dial, the Cartier Crash Tigrée Metamorphoses features enamel on its bezel, too. Here, artisans extensively used enamelling to amplify or, at times, complement other artisanal techniques. The nuances of colour are expertly captured through opaque, translucent or gradated enamelling on various surfaces such as silver paillettes or in engraved recesses of the stripes (also known as champlevé enamelling). Enamels in shades of blue and green used in this reference are achieved with cobalt oxide (for the blue) and copper oxide (for the green).

Etruscan granulation, filigree and flamed metal are techniques that fall under the art of metal. The former dates back to 4 BC, when the Etruscan civilisation popularised the decorative technique that involved tiny beads lining jewellery surfaces. Gold wires are first heated before tiny pieces are cut into water-filled crucibles. The rapid cooling shapes the gold pieces into spheres, which are then sieved and sorted according to size. While soldering the beads to form patterns is the first application that comes to mind, an innovative use of viscous liquid, sapphire dividers and gravity to form the panther head outline seen in the captivating Révélation d’une Panthère is a demonstration of the maison’s creativity.

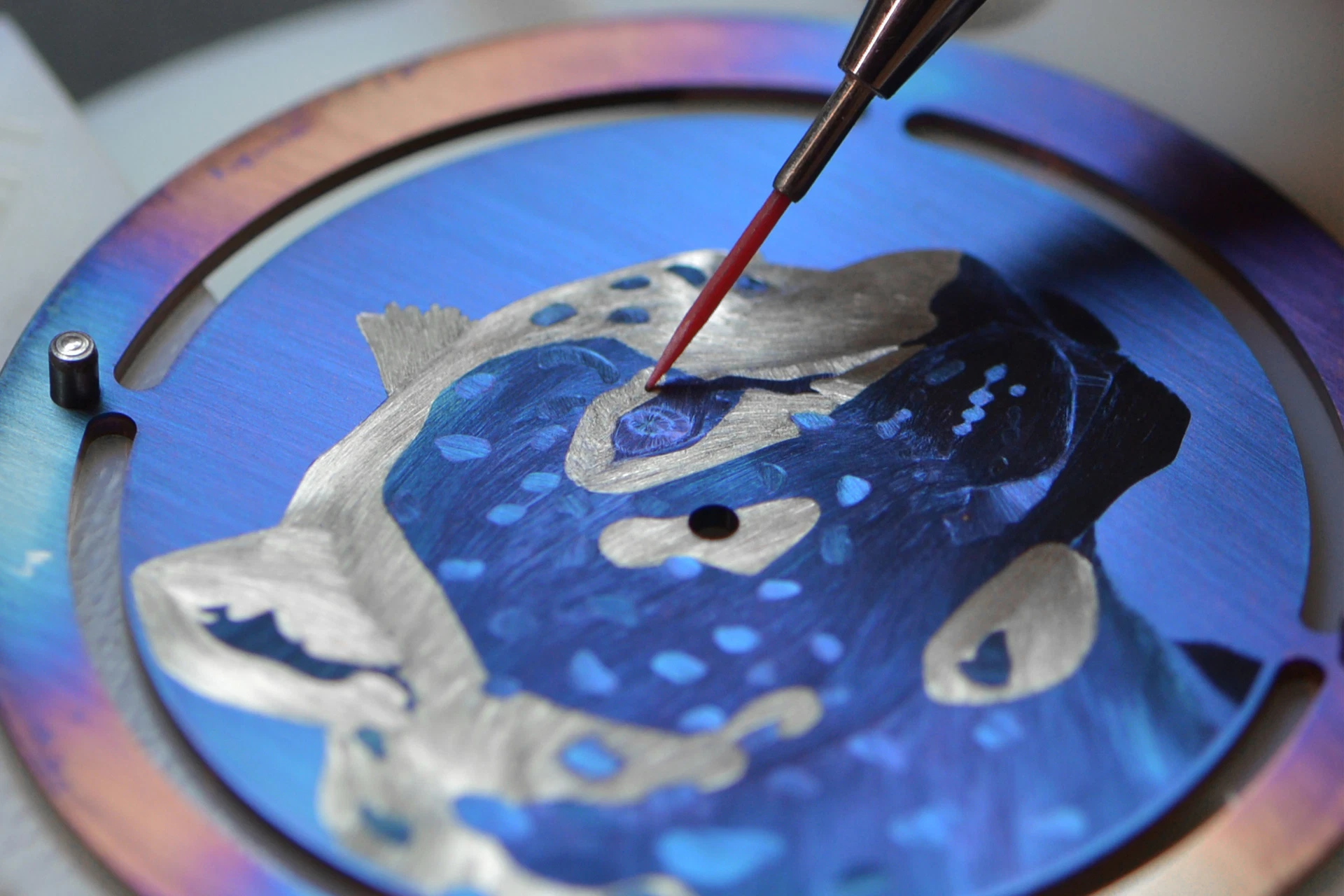

Flamed metal — one of the department’s newer Métiers d’Art techniques — involves heating metallic surfaces to achieve different colours through oxidation. The process begins with heating the dial plate to achieve a uniform blue hue before unwanted parts are scratched off to create motifs of Cartier’s famed menagerie. Artisans then mask the blued portion before heating the dial plates to achieve different shades of brown ranging from beige to dark brown. Given how such oxidation processes are irreversible, the difficulty of the technique is compounded towards the later stages of flaming. It takes a skilled eye and understanding of the craft to know the exact moment to stop the firing process. Cartier’s final art of composition is perhaps one of the most unique techniques as mosaics and marquetries involving wood, straw, flower, wood and gold, and straw and gold come together to create a watch dial. Seemingly random shapes and mismatched colours are composed together to create abstract or realistic motifs.

As the Maison des Métiers d’Art celebrates and reflects on the past 10 years, the artisans continue dedicating themselves to works of beauty and are united to meet the Maison des Métiers d’Art’s mission: to preserve, innovate, and share its exceptional expertise. Given that some techniques were on the brink of extinction at one point, there is hope that these time capsules of yesterday will be kept safe and passed on for generations of tomorrow.

This article was first seen on Mens Folio Singapore.

For more on the latest in luxury watch reads, click here.