The Downsides of Le Michelin Guide and its Coveted Stars

Michelin’s pomposity and imposition of standards act like a straightjacket for chefs, shackling them to the menu and practices that earned them each star and creating an industry without growth, personality or flare.

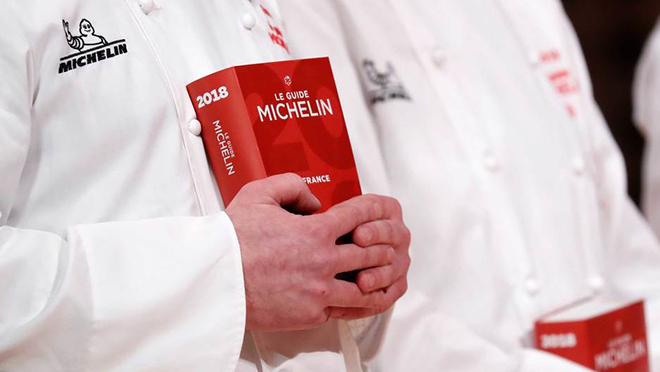

Decidedly one of the highest symbols of status, professionalism and honour a restaurant can attain, the coveted Michelin star is what chefs worldwide would strive relentlessly all year round in hopes of attaining.

While best known for its tires, the Paris-based Michelin brand is also famous for its annual Michelin Guide, an online travel encyclopedia in support of local and international attractions, aimed at inspiring road trips. Initially published in 1900, the Michelin Guide only began incorporating a star system in 1926 — emphasising the quality and flavour of food, mastery of culinary techniques and personality of dishes at restaurants seemingly overlooked or hidden in plain sight.

Despite its primary focus on the European region, in 2005 the guide published its first United States edition and soon the stars had spread across the globe — making Michelin stars the hallmark of fine dining by many of the world’s expert chefs and restaurant patrons.

Chef Andrew Pern

According to Andrew Pern, chef-owner of The Star at Harome, upon receiving a Michelin star, the restaurant’s turnover went up by an average of 22 per cent each month and 60 per cent overall. While Chef Pern describes the Michelin Guide as a “seal of approval” which massively alters both team morale and public perception.

Despite reports of Michelin star recipients experiencing a significant increase in restaurant traffic, business and media exposure, not everyone seems as eager to be part of the Michelin guide. The innumerable perks aside, certain disapproving chefs consider the rank system one of the cruellest tests in the world, forcing chefs to work year-round for a defining moment they will never know is coming or has passed.

One of France’s most acclaimed chefs and the man behind Le Suquet restaurant, Sebastien Bras has held three honourable Michelin stars since 1999. Upon voluntarily surrendering the stars, Bras expressed his exhaustion for maintaining the exacting standards of an anonymous judge, “You’re inspected two or three times a year, you never know when. Every meal that goes out could be inspected. That means that, every day, one of the 500 meals that leave the kitchen could be judged.” In 2005, the late French chef Alain Senderens also retired his stars in an effort to have “more fun” without “feeding (his) ego”.

Chef Eo Yun-gwon

Since then, South Korean Chef Eo Yun-gwon has been one of the few that have rallied against the Michelin system. Suing the company for including his restaurant “Ristorante Eo” in their 2019 guide to Seoul without his consent. Eo has taken legal action under South Korean public insult and libel laws. Accusing the Michelin Guide of forcibly listing restaurants against their will and without a clear criteria, Eo is sceptical of the guide’s tight-lipped process in judging and maintains a strong belief that a handful of restaurants should not single-handedly be representative of a nation’s cuisine or culinary expertise.

“Including my restaurant Eo in the corrupt book is a defamation against members of Eo and the fans. Like a ghost, they did not have a contact number and I was only able to get in touch through email. Although I clearly refused listing of my restaurant, they included it at their will this year as well,” Eo wrote in a Facebook post.

While the ethics and candour behind gaining a star remain questionable, the effects of losing one, if not all, are clear as day. The cloud-nine high and success that often come with earning stars can plunge quickly with every loss. De-starred restaurants reportedly witness business nosedive almost instantly, placing great pressure on staff which may send some spiralling.

- READ MORE: From Haute Couture to Haute Cuisine

The Michelin Guide ranks restaurants in accordance with the following criteria and categories:

One star: The restaurant is considered very good in its category but is limited in some way. This restaurant has a quality menu and prepares cuisine to a consistently high standard, but it may lack a unique element that would bring people back over and over again.

Two stars: The restaurant has excellent cuisine delivered in a unique way. This restaurant has something exceptional to offer and is worth a detour to visit while travelling.

Three stars: The restaurant has exceptional cuisine and is worth a special trip just to visit. Rather than being a stop on the way to a destination, this restaurant is the destination. This restaurant serves distinct dishes that are executed to perfection.

Judged by a panel of anonymous food enthusiasts with an eye for detail, these “inspectors” are prohibited from speaking to journalists and are encouraged to keep their line of work a secret even from close family members. An inspector’s job scope includes writing a comprehensive dining report on the restaurants visited — factoring in aspects such as food quality, presentation and culinary technique, while disregarding subjective elements such as décor, table setting and service standard. Each review is then followed up by an in-depth discussion amongst inspectors before shortlisted candidates are then awarded their stars.

Preaching the highest standards and venerated for creating the culinary hierarchy, outspoken ex-inspectors have since dented the polished Michelin brand name. When former inspector, Pascal Remy was sacked for keeping detailed notes whilst on the job, something we’d assume was necessary and commonplace, he immediately went public — spewing shocking behind-the-scene truths of the esteemed Michelin Guide.

With over 10,000 qualifying restaurants and five inspectors in France alone, Pascal Remy admitted to not having visited the majority of them, despite Michelin’s claims of yearly reviews. Perhaps, based on this information, the revelation that a specific list of top-tier restaurants was deemed “untouchable”, allowing it to retain its three stars no matter how far they slide — is not so surprising. The former inspector went on to admit that at least one-third of Michelin’s three-star restaurants no longer meet the criteria. Despite briefly contesting Pascal Remy’s claims, Michelin has yet to provide any form of evidence to prove otherwise.

Chef Marc Veyrat

In 2019, French chef Marc Veyrat became the first chef to sue Michelin after his restaurant was downgraded from three stars to two. He wants the mysterious company to be more transparent in its grading as well as to disclose the names and backgrounds of the people who have worked on the annual guide. Veyrat has a résumé of collecting a total of nine Michelin Stars in two restaurants and the loss of a single star sent him into a deep depression. Similarly, Chef Pern described the loss of his Michelin star as “twice as destroying” and the late Chef Bernard Loiseau was ready to commit suicide in the event his stars were taken away.

Chef Gary Pearce

In other cases, such as of Head Chef Gary Pearce who recalls when Ramon Farthing’s 36 on the Quay lost its star after 28 year consecutive years. Describing it as a confusing and directionless point in time, Chef Pearce even stated that the Michelin Guide failed to offer any feedback or explanation for its decision, leaving the entire team feeling gutted.

For the updated guide just released in 2021, Singapore’s Hawker Chan has lost its star after being award in 2016. Its soy sauce chicken rice holds the title of serving the cheapest Michelin-starred dish in the world and this recognition set the humble stall for global fame. Hawker Chan has since expanded to other countries including Australia, the Philippines and Kazakhstan.

In response to losing its star, a representative from Hawker Chan said it “understand[s] that everyone has their own opinion when it comes to food choices”. Taking the results as a pinch of salt, the team “will continue to serve delicious and affordable meals as that is our vision and mission”. It looks forward to earning back the lost star in the next round of assessment. But with or without the star, the stall is still highly popular among the locals and a snaking queue remains a common sight.

Beyond the pressure to maintain a consistent set of “undisclosed” standards, restaurant owners face a litany of social and economic issues. When the Michelin Guide first expanded into Hong Kong, grateful and honoured businesses experienced an increase in rent by as much as 120 per cent, while other local street food stalls faced prejudice and anger for drawing crowds into quiet local communities.

- READ MORE: ESG Vs Food: A Delicate Balancing Act

While it is perfectly normal for the rankings of any “exclusive list” to fluctuate, the consensus held by both sides who support and disapprove appear to be consistent. The secrecy surrounding the Michelin Guide’s operations and criteria have a significant impact on the wellbeing and growth of restaurants and other smaller establishments — making the process of maintaining success, expensive and constraining with little room to be experimental and creative.

With its limited scope, the Michelin’s pomposity and imposition of standards act as a straightjacket for chefs, shackling them to the menu and practices that earned them each star and creating an industry without personality or flare — where every Michelin restaurant boasts cloying and oleaginous service with vast menus clotted with verbiage and an atmosphere gravely silent.

For more gastronomy reads, click here.