Interview: Artist Michaël Borremans

Art Republik eases up to the unsettling works of Michaël Borremans.

Michaël Borremans is a Belgian artist whose oeuvre is as mesmerising as it is mysterious, and as a human being, as delusional as geniuses get. Sitting down with Art Republik, Borremans tell us that he has a country studio especially for guests, equipped with a wood-fired sauna, and a bathroom, which he proudly designed himself, made of marble and mirror — “it is decadence,” Borremans boasts. Already, true to his paintings, we are at once awestruck yet uneasy.

Borremans was born in 1963 in Geraardsbergen, Belgium, and currently lives and works in Ghent. In 1996, he received his M.F.A. from Hogeschool voor Wetenschap en Kunst, Campus St. Lucas, in Ghent. As an artist, Borremans currently specialises in painting with a technical command of the medium that recalls classical painting, reminding one of the Old Masters such as Francisco Goya, while at the same time having started out in drawing, and recently experimenting with film.

Since 2001, the artist’s work has been represented by David Zwirner. Previous solo exhibitions at the gallery in New York include ‘The Devil’s Dress’ (2011), ‘Taking Turns’ (2009), ‘Horse Hunting’ (2006), and ‘Trickland’ (2003), which marked his United States debut. His most recent solo exhibition, ‘Black Mould’ (2015) marked his first solo presentation at David Zwirner, London, and his first solo presentation in the city in 10 years.

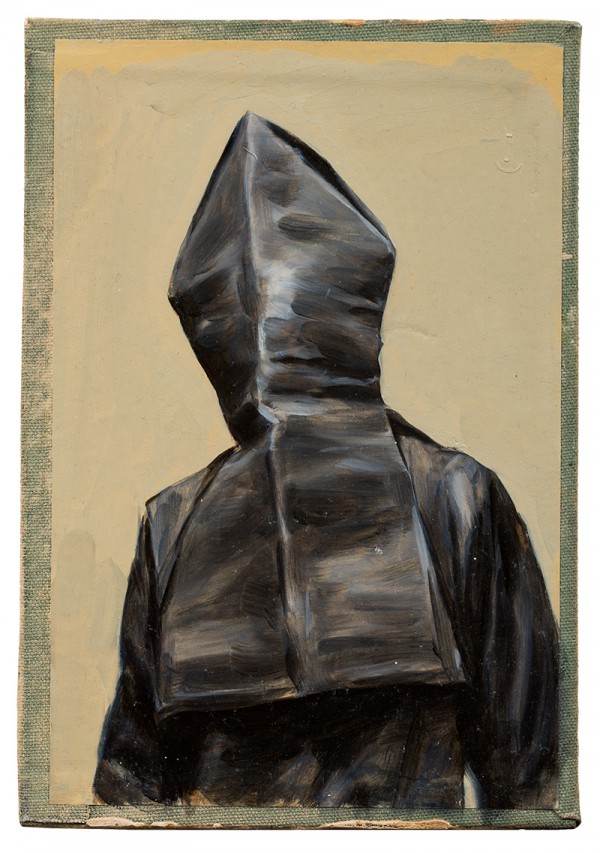

Michaël Borremans by Tim Drivens

- READ MORE: Romain Langlois: Artist and Alchemist

Looking at his latest body of work in relation to the artist himself, ‘Black Mould’ consists of varied-sized paintings that feature anonymous, almost zealous, almost cult-like, black-robed characters. These unidentified individuals parade across the series performing, posing and dancing either alone or in groups, as if void of normal human behaviour. It’s impossible to look away as curiosity slowly kills the viewer. David Zwirner gallery notes that “there is a theatrical dimension to his works, which are highly staged and ambiguous, just as his complex and open-ended scenes lend themselves to conflicting moods — at once nostalgic, darkly comical, disturbing, and grotesque. His paintings display a concentrated dialogue with previous art historical epochs, yet their unconventional compositions and curious narratives defy expectations and lend them an indefinable yet universal character”.

“The archetypal Borremans painting is a seductive enigma, a bouillabaisse of specificity, obscurity, anxiety, humour and great technique,” reviewed Martin Herbert for ArtReview. True enough, the atmosphere surrounding ‘Black Mould’ stays consistent with Borremans’s oeuvre, dramatic yet purposeful, with an open window into another world or universe that is somehow imaginary yet familiar, leaving the viewer feeling uneasy but inspired. Additionally, the elusive reality of the series seems both current and timeless; the secrecy of the subjects and the setting may initially be seen to underscore the ritualistic nature of human life across centuries and cultures, but on closer inspection, may also signify discourse within today’s society of morality, faith, hegemony and even politics.

Borremans’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at numerous globally prominent institutions such as Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels; Tel Aviv Museum of Art; Dallas Museum of Art; the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo; and de Appel Arts Centre, Amsterdam. Work by the artist is held in public collections internationally, including The Art Institute of Chicago; Dallas Museum of Art, Texas; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia; The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (S.M.A.K.), Ghent; and the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Art Republik slowly warms up to our issue’s cover star, Michaël Borremans, who candidly speaks to us about his career, his philosophies and the meaning of life.

Being both a painter and a filmmaker, which comes first for you? Can you discuss the difference between the narrative in painting and in film?

Oh I’m a painter, I’m not a filmmaker. But I’ve been using the medium of film to extend what I’m trying to do with painting. I don’t see myself as a proper filmmaker. And my use of film has been very limited in my oeuvre. Actually, I see myself as more of a sculptor, because most of my work are based on ideas as a sculptor and eventually, I hope to create a sculpture of my own. But what I prefer about paintings than sculptures is that paintings are a window into another reality, whereas sculptures are in our reality. That’s why I try to depict my sculpture ideas using other media.

Tell us more about this detachment from reality that’s very apparent in all your work.

I find what I like so much about painting, from since I was a little boy, is that they’re so mysterious. They are like a door or window to a place you cannot enter, but you can see. And I still use this aspect strongly in all my work.

You’ve mentioned that “the direct gaze is pointless. The painting would then become a portrait”. Why do you not consider your paintings portraits?

Well I use the classical formats like the portrait, the nude, the still life because I want to bring something into the painting that is very recognisable to the viewer, but I change something within it, and then it becomes more like a general image of a human condition. So it’s also important to note that the figures in my paintings are not individuals, they are general figures.

With the ambiguity of your subjects, do you usually draw inspiration from something or someone specific first?

It’s always a different story with every painting. Sometimes it’s a dream, sometimes it’s from something I remember seeing. All my works have their own origins.

You were originally trained as a photographer and still take photographs that you use as reference for your paintings. What is it about photography as a medium that doesn’t interest you anymore?

I’m not a social person and if you’re a photographer you have to come out and be social and it wasn’t for me. I’m the type of artist who likes to stay in and be in my own world.

How does photography differ from painting and also film?

A photograph is a very transparent medium. If you look at a photograph, you look at the image first, you look at what you see in the photograph; you never think, “Oh the photograph is an illusion.” But you always think this of a painting, you know you’re looking at a canvas, whereas with a photograph or video or when you watch television, you look at the facts, you don’t look at the medium. And I like that the painting provides this closeness and that the world that is depicted on the canvas is imaginary.

There seems to be a purposeful dullness to your paintings, yet a paradoxically strong message in the mundane. Can you tell us more about that — the frequent use of unsaturated colours?

For one I started out in drawing, I only started painting late when I was in my mid-30s, so I come from a black and white world. The colours only came in slowly. And because for me, I want to create an atmosphere in the paintings, and too much bright colours will interfere with my ideas of atmosphere, especially that dark colours create a very theatrical atmosphere. And when I do uses colours they have a very functional purpose and only when I need it, but I still try to limit my use of them as they would distract too much from the image.

Would you say the use of colours also follows your state in life? How beautiful is life to you?

Well I’m not the merriest person. Life is a tricky thing, it’s very ugly and beautiful at the same time, very attractive but not; that’s what I try to tell in my work. I have strong double feelings about life. I think when we die we should be happy that we can die — it’s good that there’s a way out.

You can do two things in life: you can do things that you love, that you find attractive and fun, or you can just stare into the void and commit suicide. It’s a choice everybody has to make. But I’m not afraid of living, and I want to live at high levels; in a simple way, without great demands, but to be able to work, to do what I love. Before I became an artist I was an art teacher, teaching drawing for 10 years till 2000, but it was only to make ends meet. I am happy that I have art now.

If not art, what would you be doing?

A car mechanic, though I don’t think I would be any good at it. But I’m crazy about cars. I love old cars, they are like sculptures when well-designed. I recently acquired a Jaguar E Type myself. Oh it’s amazing, especially its smell, it smells like an old shoe shop from a childhood memory.

This article was first published in Art Republik.

For more art reads, click here.