Artist Natee Utarit: Lights Out

Natee Utarit shows us that life’s not always rainbows and butterflies.

“Samlee is a Bangladeshi magician. Formerly known as Kasim, he and his family started coming to my studio, where he modelled for my paintings, since 2014. In fact, Samlee had achieved a certain degree of fame in Thailand as a member of the Philip Magic Troupe some twenty years ago.” So begins the wall text for the sold-out solo exhibition of Thai contemporary artist Natee Utarit’s latest series of artwork at the booth of Richard Koh Fine Art at Art Stage Jakarta 2016. Interestingly, the text is written not by a curator but by the artist himself, who goes on at some length to write about the magician’s unfortunate, premature retirement from his career, and the circumstances that brought Natee to paint him and his family.

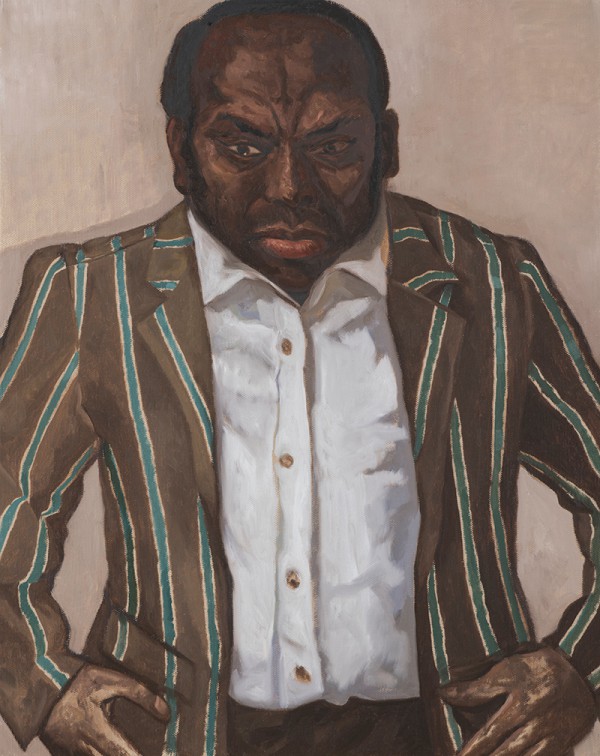

Natee Utarit, ‘The Magician King’, 2016, oil on canvas,

90.5 x 68.5 cm. Courtesy of Krisada Suvichakonpong and Richard Koh Fine Art.

To tell Samlee’s story, Natee asked the young Thai artist Krisada Suvichakonpong, who had photographed the making of his ‘Illustration of the Crisis’ series earlier in 2013 to photograph the time that the artist spent with Samlee and his family in the studio. “When I decided to paint this magician and his family, I thought that it would be great if I could tell more of the story regarding my painting process to explain how I collaborate with them as models,” says Natee. “The final photos were selected from hundreds of shots showing different moments between the artist and the models during a seven-day period in the studio. For me, it is quite amazing to capture Samlee’s character and his personality and then communicate the whole story with both the paintings and photobook.”

Beckoning fairgoers to the booth are the words ‘Samlee & Co. The Absolutely Fabulous Show’ in a grand carnival-esque font. The 18 paintings, completed this year, look like prints of charmingly imperfect hand-painted circus posters. While most of the paintings feature Samlee, such as ‘Blue Stripe’ and ‘Pietà’ there are also other subjects, including Samlee’s children in ‘Magician’s Daughter’ and ‘Moody Boy’, as well as Samlee’s props as a magician in ‘George’ and ‘Jog’. The paintings all like posters that might once have been vibrantly coloured but now look smudged and gritty, and feature unsmiling faces, seemingly in reflection of the life story of Samlee, whose 15 minutes of fame ended all too quickly.

Natee Utarit, ‘Billie Jean’, 2016, oil on canvas, 90.5 x 68.5 cm. Courtesy of Krisada Suvichakonpong and Richard Koh Fine Art.

The rough-hewn quality of the portraits may seem incongruous with Natee’s signature realist paintings. However, this is not the first time he has produced works that have been purposefully treated to look less than perfect. In ‘Reasons and Monsters Project’, realised in 2001-2002, he stained his paintings based on Old Master paintings from Titian and Caravaggio to question traditional notions of beauty in Western art. He did the same in another series ‘Last Description of the Old Romantic’ in 2005, which featured floral still-lifes taken from classical paintings.

The rawness of the paintings in ‘Samlee and Co.’ captures the imperfect humanness of his subjects, and reflect the introspective nature of the work. “They had a very personal touch to them and it wasn’t really about the people he was painting,” says Richard Koh. “Natee, every now and then, does a small body of work that has a very personal narrative to it and most times, it just records his thoughts and emotions at that point in time.”

Indeed, it appeared that the meeting with Samlee and his family threw up questions for the artist about impermanence in life, as well as the trials and tribulations that everyone inevitably has to go through. “Samlee and his family are very interesting, and they have made me search for an answer for the existence of life in the world today,” says Natee. “His personal character reminds me of old stars who try very hard to make a comeback in the real world. I can see all of this from his family, from his magic objects and props. Everything looks wrong and it’s not easy… really not easy.”

A particularly poignant line in the artist’s wall text for the exhibition is “nothing is arbitrary, there are no miracles and there is no magic, and above of all, nothing is unilaterally true”, a rather pragmatic, pessimistic outlook on life as seen through the personal tragedy that Samlee has lived, and one that the artist empathically portrays in this body of work

This article was first published in Art Republik